Steve Byrum, PhD

Founding Partner of Judgment Index

One of the most important “rites of passage” growing up in the 1950s and 1960s was not your first car or your first date. Very early on your hopes, dreams, and ambitions—all forms of valuing—were focused on bicycles. The bicycle was a source of great fun and great freedom. You knew every brand of bike available in your hometown stores, and the “coolest” kids in the neighborhood had shiny bikes that gleamed in the summer sun and could ride the bikes in ways that would make a circus performer jealous. Although most of us would have hand-me-downs from older siblings or bikes created from varied pieces of bikes picked up by our mechanical-gifted fathers, we studied the Sears-Roebuck catalog or peered in the windows of the local Western Auto Store to look at the newest, finest Western Flyers and Roadmasters. One boy from across town—the “rich section” of our community—even had a Schwinn Phantom with hand brakes; we looked on with awe and respect when he parked at the school bike rack.

In those days, at least at my house, you did not learn on a child’s bike at three or four. I don’t even remember ever seeing a child’s bike like my wife and I got very early on for our children. You learned on a 36” wheel bike that was your next oldest brother’s when he graduated to a car. At first, you could not even sit on the seat and peddle at the same time; your legs were not long enough. You did know every part, how it all worked, and how to mechanically ride. What you didn’t know about was balance—as it turned out, the most important aspect of riding successfully.

So, there was a several-day period—maybe even a week or more—of trial and error, mostly error. There were skinned knees, embarrassing falls in front of my peers, and I would even wait until the dark of late evening to try and try again; not a very good idea in our section of town where the streets were ill-lighted and filled with potholes. Knowing all you came to know about bikes, even how to quickly repair the tires that seemed to always be picking up a nail, was pretty easy. Being able to talk “bike language” made you seem like the “expert” that you certainly were not. None of this mattered all that much without balance.

And then, when balance came, it was an amazing, lived experience; an existential and intrinsic event well before you had even ever heard those words. The lived experience of balance gave me pure joy. The experience was what the philosopher, William of Ockham, way back in the early Middle Ages would have called a “felt reality,” an event never capable of being put exactly into words or explanations or definitions. Ockham talked about “an experience of first intension,” an “inner-tension” that made you and the bike become almost one. And, with balance, came a new sense of freedom which only got better—you learned intricate tricks that took mere skill to a next, exponential level, and you got paper routes that you did not have to walk with greater range and more customers. I can even recall riding my bike twenty miles to see the girl I had fallen in love with; no small accomplishment as there were plenty of high hills between where we lived. It must have been my biking that paid off as we have now been married for over fifty years. Balance can definitely have its rewards!

At this point, I can transition a bit. Before refocusing attention on balance, what I have said about biking to this point provides a really good opportunity to understand a basic level of insight about the work of Robert S. Hartman and then the assessment instrument he created. First, take note of how very early on I was “noticing” bicycles, even to the point that they were becoming a distinct object of what I called above my hopes, dreams, and ambitions. Seeing myself on a bicycle had become an important part of what Hartman saw as “Self-image,” how we see ourselves moving into the future, our “projected Self.” This “Self-image,” as he explained, translates into motivation, following our dreams and projections. We move from “present state”—unable to ride—to “desired state”—flying like the wind with skill and balance totally merged in a beautiful moment in time.

Dr. Robert Hartman is the creator of the Judgment Index assessment. He was a German philosopher who developed the formal axiological system, which provides a mathematical framework for analyzing and measuring values. Hartman’s work focused on the structure of values and the logic of value judgments.

Then, note that I emphasized above that this entire process is a values process. We come to establish certain goals, for example, that are valuable to us. We do a great deal of e-valu-ating as we refine these goals. Who we were as human be-ings1 at that time in our lives, much as it is the same today, was defined in terms of values and valuations, much more so than in terms of rational intelligence, psychology, or personality; we were—and are—values-driven, and the more you understand our value systems, the more you recognize what and who we really are. Hartman believed that this entire sense of a human be-ing as a values-driven and values-defined person was axiological, from the Greek axia means “worth” or “value.” All that I have said above totally adds up when you recall the sense of “Self-worth” that balance on that bicycle brought to your life.

So, Robert Hartman taught in his axiology and learned to bring measurement to his assessment instrument in three dimensions of evaluative experience:

- The Systemic—when we conceptually know the general basics of some matter—our first, initial information about what a bicycle is, what it can do, what it is basically about as one object among others in the world

- The Extrinsic—when we have real, recognizable information that allows us to discriminate and define in terms of a real-life object in the world—recognizing the difference in a Western Flyer, a Roadmaster, a Schwinn—recognizing different working features like brakes or balloon tires compared to the admired, narrow Schwinn tires—recognizing the difference between “girls’ bikes” and “boys’ bikes”

- The Intrinsic—the experience of riding as fast as the wind, flying down steep hills, or amazing friends with daring tricks—the thrill of winning a school bike race—even the misery of coming in second in a race where your number one “rival” won the day on his Schwinn Phantom with the narrow, racing wheels.

Hartman gave me a perspective with this “Hierarchy of Value” that has changed the way I have looked at life, looked at other people, and even come to look at myself. I want to be efficient and effective in the useful Systemic and Extrinsic, but—even more—I want to experience the Intrinsic, the “felt” of life, the “in-tension” of life. Hartman put it all into words for me when I was about 20 years old, but it was all there with that first bicycle, but it never would have happened without balance. So, Hartman had no problem speaking to the importance of the strength of a person’s evaluative judgment, but he knew that strength without balance would always fall short and be inadequate to what was possible in life. In his assessment, he devotes huge amounts of emphasis to strength but saves his highest emphasis for balance. It is balance that allows strength to rise to its highest potential. It is balance that opens the door of highest achievement and worth of strength. It’s like riding a bicycle—when we get to balance, we are really going somewhere!

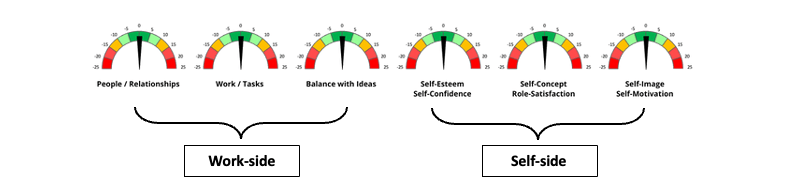

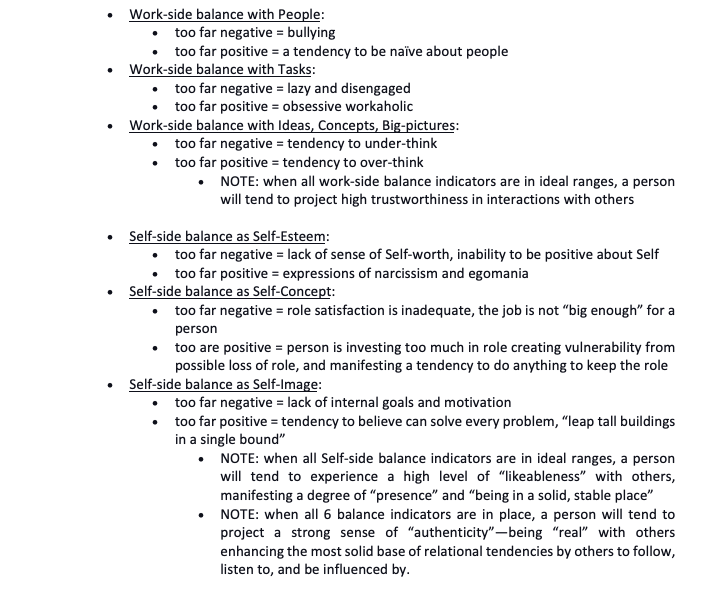

The way that balance is measured in the assessment is quite easy to understand. There are six areas given consideration, three on the work side of the assessment and three on the self-side. The potential range of scoring runs what Hartman calls a “transposition,” an undervaluing inadequacy of importance to a “composition,” an overvaluing exceeding of importance. The ideal is to hit a middle, balance range. The meanings attached to the scoring patterns are fairly simple to grasp as they are frequently evident in modern life circumstances.

These six areas of emphasis and the measures that go with them have never failed to help advance some of the most compelling and change-advancing conversations about development and growth, and particularly leadership development and growth, that I have ever experienced. The numbers related to balance in Hartman’s presentation can become a profound instance of awareness, and the kind of awareness that can be a real catalyst for positive change.

Now, what I would like to do in conclusion is to contextualize Hartman’s insights on balance within a larger context of human consideration that has been jumping to the front of “great ideas” and “great insights” that span the centuries of human enlightenment about what is actually most important in life. In creating this expanded context, Hartman’s work is not only greatly complimented and affirmed, but he can be seen—especially in the analytical data of his assessment—as advancing a very vital conversation in new and more exacting directions. Hartman’s work can be seen as part of a central focus of human consideration that has been peaking around the idea of balance for a very long time.

We can first touch base with Aristotle (384-322 BC) whose work touched almost any and every area of consideration about human life. But, at the core of his thought, Aristotle was concerned with how people lived their lives and the possibility of actually achieving happiness. He insisted on the importance of achieving equilibrium—his word for balance. This equilibrium was found somewhere in the midst of trying to walk the “Middle Way” (sometimes spoken of as the “Golden Mean”) in life. This middle path, and it was a lifelong journey, was crafting a way between extremes. His emphasis could take many forms:

- the balance between excessive greed and depravity;

- the balance between putting Self first in a purely selfish and self-serving manner, and being totally subservient to the needs of others;

- the balance of body, mind, and spirit.

Aristotle also identified this kind of balanced life that would lead to happiness with “virtue” (the Greek arete) which he identified as the most important “balance” that could be achieved. At the same time, “virtue” meant the way that we ethically and morally lived towards others, but it also meant the fulfillment of one’s own “appropriate excellence,” what Hartman might call one’s own “uniqueness.” Here was a balanced approach with emphasis on being “true” to others in a respectful and care-filled way, but also being respectful of Self and fulfilling one’s own uniqueness in the context of high Self-understanding and high Self-awareness. Here we also see the intrinsic intertwining of Hartman’s mutually inclusive achievement of personal uniqueness and serving others. When this balance manifests in happiness, Aristotle called it the “activity of the soul,” an experience of Self roughly equivalent to Hartman’s intrinsic value experience of Self-fulfillment.

Move to almost the other side of the world, even predating Aristotle by about 200 years, and you come to the philosophy of Lao-Tzu (in some more modern spellings, Laozi), a contemporary—at least in legend—of Confucius and Siddhartha, the Buddha. Lao-Tzu taught about the possibility of achieving a quality and beauty of living that allowed for the experience of “The Way”—in the ancient language of his way, the “Tao” which is often spelled today as Dao. This “Tao” is a way of life, a way of be-ing in the world, a state of be-ing in the world that has all of the earmarks of fulfillment and happiness. Unfortunately, in the race to power and dominance taken up by most people, this “Way”/”Tao”2 is missed. As with Aristotle and Hartman, the critical ingredient in and the ultimate confirmation of existence along this life’s-journey “Way” is balance.

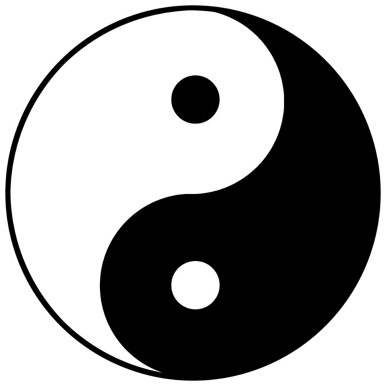

It is Taoism that provides the iconic Yin-Yang symbol that advances the idea that there is good and bad, right and wrong, light and dark and that the perpetual challenge of all of life is to keep some kind of constructive and functional balance between extremes. It is at the extremes, just as in Hartman’s balance indicators, that a compromising and even destructive “wobble” and “shaking” can occur that throws all of life out of sync. The Yin-Yang symbol also implies that there is light/good in the darkness somewhere if it can be sought out and discovered. There is also darkness even in the brightest light of goodness that can be threatening and must not be overlooked.

In the end, Lao-tzu had his fill of teachings, philosophies, belief systems, and religious and political establishments. He believed that most of these kinds of expressions and the activities that followed them were not advanced in order to achieve greater harmony and balance, but rather were all too often the medium and mechanism of personal gain and tribal power. All too often, out-of-balance greed on one side of life created great deprivation on the other side of life; humanity divided between “haves” and “have-nots” could never rise to the level of “civilization.” He left China to live a life of “creative withdrawal,” believing that such a life would bring greater happiness to himself and others so inclined to follow his “Way.” Only because a perceptive guard3 at the Great Wall—according to legend—recognized him and required writing down his thoughts before being allowed to leave do we have today the great Taoist text, the Tao Te Ching (also spelled as Daode Jing). A typical, standard translation reads The Classic of the Way and the Power. However, care must be taken here because the word translated as “power” carries all kinds of connotations of militaristic and political power that is aggressive, dominating, and malignant in its impact. To me, the most accurate and finest translation of the somewhat ambiguous, Chinese word leans in the close direction of Aristotle’s word virtue, arete. Without any question, Lao-tzu’s “Way” of living, the state of be-ing he aspires to as ideal, is a way of virtue that advances and sustains balance in living. To have this balance and advance it in society, then, clearly would be an unabashedly “powerful” Way of living.

To me, it has always been a wonderful teaching exercise to ask a student to take the Tao Te Ching, read it, and mark passages that were particularly meaningful or that “spoke” personally to the student. Without question, asking students to explain why particular passages stood out creates a very interesting conversation with others, but—more importantly—the kinds of “conversations” of Self-awareness that can occur within a person. My strong conclusion formed early on in my teaching career that this exercise was purely axiological since what the students underlined and highlighted ended up being reflections of their own value orientations. Here, then, are a few Taoist quotes that have risen from my own underlining:

- The person who clings to his work will never create anything that lasts.

- People who need to prove their point are not wise.

- A good traveler has no fixed plans. He is not intent on arriving. So, he sees things along the way. His trip is not ruined by interruptions.

- Presuming to know creates dis-ease.

- The person who knows he has enough is rich.

- Trying to rationally understand is like straining muddy water. Be still. Allow the water to settle.

- The Tao that is named is not the ultimate absolute. The Tao has 10,000s of names. The nameless, the refusal to put into words, is the beginning of heaven and earth.

- The clod of dirt beside the road knows more about the Way than most people.

Finally, there is one ancient stopping place of consideration that must be mentioned relating to this critical concept of balance. In the New Testament writings attributed to Paul (Saul of Tarsus), there is an emphasis on “the grace of God.” It is a typical Christian theme that almost always means “unmerited favor” that rises from the love of God which is extended to all people in the form of help, understanding, and forgiveness. Paul would certainly embrace these traditional ideas. However, in almost all of his writings, he turns regularly to the use of athletic metaphors of explanation. Grace for Paul, then, means a certain “gracefulness of living” in balance. His grace is an active way of living in the world, almost like the tight-rope walker or the gymnast on the balance beam. To live without falling, without losing balance, produces a highly desired style of life, a way of be-ing. There in this grace-full-ness was the possibility of achieving a form of happiness that transcends most happiness.4 This grace-full-ness is dependent on a way of virtuous living with others rather than any sort of theological construct or particularized church discipline or organization.

For the modern reader, if much of this discussion sounds to you like a major theme in the Star Wars saga, you are exactly right. The “Force” is the source of the energy that becomes the catalyst for all actions. Obviously, “Force” is an intrinsic word much like “Spirit” or “Energy.” This “Force” seems to animate every factor of life that may be cumulative over generations, and rises primarily from human decisions and the achievement of human potential. The word “Force” is simply a word, not all that different from the Tao in that the “Force” that is named, explained, and defined is probably not the “Force” at all but rather a reductionistic, rational concept. The “Force” is what the medieval philosopher, William of Ockham, as we saw in our initial statements, called a “felt reality.” It can be intrinsically experienced, but when it is put into words it is lost—and worse, becomes the possession of some cultural interpretation that people are usually called upon to unquestionably embrace and defend. The idea of a “felt reality” at the introduction and conclusion of this essay accentuates its importance; the highest realities of life are intrinsic, ineffable, and beautiful in ways that profoundly transcend rationality and mere “thinking.”

In the Star Wars saga, the “Force”—like most religious conceptions—has been sought, talked about, and articulated in metaphors and myths since the beginning of human consciousness. George Lucas, in conceiving the films, was certainly aware of Buddhist, Zen Buddhist, and Taoist concepts. For example, the Jedi uses forces of the “the light side”—who opposed the Sith—while on the contrary, “the dark side”—comes from the Japanese jidaigeki, the word associated with Samurai warrior movies. The seesawing of the “light side” and “dark side” becomes the fulcrum upon which the entire movie series turns.

The key point for our discussion comes from the expression “a disturbance in the Force” which appears at several important moments of crucial awareness in the films. Most prominently, introducing the critical theme in the first movie, the Sith-created Death Star with its forces commanded by the infamous Darth Vader succeeds in destroying the Rebel Alliance planet, Alderaan. Obi-wan Kenobi, the Jedi Master, suddenly slumps toward the ground, and gives one of the most memorable lines in the movie, “I felt a great disturbance in the Force as if millions of voices cried out in terror and were suddenly silenced. I fear something terrible has happened.” This “disturbance in the Force” is the awareness of a loss of balance, and when that balance is lost, forces of chaos are given space in which to work their actions of darkness and dominance. The goal of the Jedi is to restore balance, but as is seen in one character after another—but most particularly at first with the young Jedi, Luke Skywalker—there must be a finding, claiming, and sustaining of personal balance—the “Self-side”/the internal world side, to use Hartman’s words, bringing the foundation of its balance to the external world side. How telling in that famous scene where Luke steers his X-wing Fighter into the canyon walls of the Death Star that he puts his rational technology away and depends for a moment on his own balance.

References:

1For those familiar with my writings, I use the spelling be-ing with the hyphen to try to capture the verbal force of our living in the world. To me, the contrasting word being has too much of an object status which reduces the human to an object among other objects as opposed to an “actor” carrying out actions in the world. For those with more than a little dose of the history of philosophy, the distinction here is very close to what Martin Heidegger called Dasein, be-ing there, real present-tense existing in the moment/the world. This is also close to what Jean-Paul Sartre called pour-soi, be-ing for itself, primary consciousness and awareness of the experience of the present moment of one’s existence as an authentic/valued Self, and which Sartre contrasted with en-soi, being in itself, the existence of the Self as an object among other objects, defined/valued by the objective forces of nature and culture. Ultimately, Sartre wants to talk about the fact that we cannot avoid living in the world, and must always be contending with how we are seen/defined/valued and how we see/define/value our own Selves. Because there is always this vacillating, tenuous, ambiguous “connection” between world and Self, he ultimately sees existence—his “Way” so to speak—as be-ing in itself for itself.

2For those familiar with the New Testament, this emphasis on “Way” should rise to attention reminders of Jesus’ statement—in response to “Doubting” Thomas’ urgent question near the end of Jesus’ life about “showing us the way—that He (that is, His “way” of living/way of be-ing in the world) is the ultimate “way” to whatever may be seen as God, the Holy, Eternal Life, etc. It is also interesting that this “Jesus Way” has a close correlation with Aristotle’s emphases on virtue, be-ing one’s own Self, happiness, and balance.

3This story of how the book came to be written is interesting, but in reality, the book is a compilation with attribution to Lao-tzu that came into its final form over generations. This does not diminish the book in any way, and without a doubt some—perhaps many or most—section was written by the great master or written down by his followers. This process of compilation and attribution can likely be applied to almost all pieces of ancient writing.

4The normal Greek word for happiness is Eudaimonia which almost means “good luck” or “good fortune,” being especially fortunate in the way life turns out. However, there is also in the New Testament that influenced Paul the possibility of Makarios happiness, often translated as “blessedness,” a state of be-ing that is deeply experienced in balanced and virtuous living with others.